Something miraculous happened yesterday, an event reduced to a small story in an area newspaper, but a miracle nonetheless. After the House of Representatives passed a bill to overhaul education and end No Child Left Behind, the Senate likewise passed the bill 85-12. President Obama has indicated he will sign it into law

Something miraculous happened yesterday, an event reduced to a small story in an area newspaper, but a miracle nonetheless. After the House of Representatives passed a bill to overhaul education and end No Child Left Behind, the Senate likewise passed the bill 85-12. President Obama has indicated he will sign it into law

Will this end the relentless testing and return the teaching time that has been lost for over a decade? No. However, it will reinstate the decision about how to evaluate schools back to local schoolboards and to the states. That’s a first step in the right direction.

No Child Left Behind (NCLB) was passed in 2002 by President George W. Bush. That was, coincidently, the year I left public high school teaching. For me, the writing had been on the wall since the late 1980s. I could see a future educational system where students would be judged by how well they could fill in test answer sheet bubbles. With the usual stupidity of a law made by non-teachers, NCLB meant students faced no penalty for the lovely patterns they drew on their answer sheets. I watched them. I also feared that teachers would be retained or fired by how well a particular batch of students did under their tutelage. Unfortunately, that too has become part of the teacher evaluation process used currently.

NCLB created a system where the federal government directed the actions of fifty states and 13,500+ local school boards. It created a national testing system where students were tested in math and reading, and schools were penalized if their scores didn’t increase each year with totally different students taking the tests. Eventually, the penalties dictated that a governmental takeover would occur for poor-performing schools.

There is some merit to a national school system; most developed countries, other than the United States, have a national curriculum and standards. But the problem with NCLB was that every income level student, every non-English speaking student, and every student with disabilities was expected to take the same test and show progress. Often, students hadn’t had some of the course work being tested. Eventually, the testing percentages that had to be attained would rise to an impossible level. The law simply was not good for schools, teachers, or students. Businesses that wrote, developed, printed tests, and evaluated the results were the financial winners. I hate to think how much of our tax money went to paying for those tests since 2002.

The new law, optimistically titled “Every Student Succeeds,” [Sorry you cannot hear me laughing through your computer] does not rid us of tests completely. It requires that each state develop its own system for testing students in three different grade levels. The scores must still be publicly reported and sorted by ethnicity, race, income, disability, and non-English speakers. It also allows states to include such factors as academic growth in one year, parental involvement in the schools, and access to challenging courses. It is not perfect either. But it does return a great deal of control to the states and local school districts. That is where the control should be.

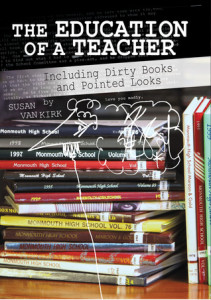

Five years ago, I published a memoir about my teaching years from 1968 through 2008. It is called The Education of a  Teacher (Including Dirty Books and Pointed Looks.) It contains a glimpse into the pre-NCLB world of teaching students in public schools, and this book is still selling. In the preface I wrote:

Teacher (Including Dirty Books and Pointed Looks.) It contains a glimpse into the pre-NCLB world of teaching students in public schools, and this book is still selling. In the preface I wrote:

“I believe it is instructive to remember such a time [1968-2002] before politicians looked for simple black-and-white numbers to describe whether schools were ‘working.’ Those lawmakers failed—as is often the case—to allocate money to cash-strapped schools so those schools could pay millions to buy tests and test evaluations in order to adhere to the law. That was the world I left when I retired from the public schools; unfortunately, that is the world my college students are inheriting. I felt it was important to give the future a glimpse of that pre-NCLB world. If educational policy history is any indication, with its ebb and flow of trends, NCLB too will pass.”

There is an old saying about revenge. Those who hurt you will eventually screw up themselves, and if you’re lucky, God will let you watch. While revenge is not on the top of my list here, I do feel fortunate that I was allowed to live to see the demise of NCLB.

Yes, I watched President Obama sign the bill this morning. It was a bipartisan (not a word heard often these days) effort, as Senators Patty Murray (D-WA) and Lamar Alexander (R-TN) were the chief architects of the new law. That fact gives ESS some level of credibility that NCLB lacked. Before coming to the US Senate, Murray had been a longtime preschool teacher, while Alexander’s father was a high school principal and his mother a preschool teacher. So both senators, but particularly Murray, have some notion of what life in the classroom is like.

The new statute’s title, “Every Student Succeeds,” is hopefully a harbinger of a brighter day in education. After all, “success” is a far more appropriately subjective concept than “left behind.” Success to one person may not be success to another; likewise, success for one student, may not be success for another student. Furthermore, measuring success by expecting all students, regardless of circumstances, to “meet” arbitrary standards on a few hours of multiple choice testing is a fool’s errand; and then when the test scores are used to evaluate a teacher’s performance, it becomes a gross injustice.

The fact that the federal government will be relinquishing some power to the states and local school districts is, in my view, a double-edged sword. Ostensibly, those closest to the community–students, teachers, parents, and taxpayers–should know what is best for local education. However, so often the states and local school districts have been the worst kind of culprits when it comes to cheating those who are the most educationally needy. We must not forget that “states rights” and “local control” have been encrypted language for “segregation,” “unequal,” “white supremacy,” and “class preference.” So, I demand that the federal government continues to keep a ladle in the stew, because I want every student to have at least the change to succeed, unimpeded by the worst of tyrants: the ones closest too us.

What I really demand, is that our nation truly put a premium on education by putting our money where our mouth is, especially in those schools who have the most educationally needy students. No one can make me buy the BS that “money doesn’t matter.” If money doesn’t matter in education, then why do the wealthy spend so much of it sending their kids to the priciest prep school in the nation? Of course, it matters, and the more of it we spend wisely, the better chance our children and young people will have of truly succeeding.

I do, though, agree with Sen. Al Franken (D-MN). This afternoon on MSNBC, Franken said that the ESS is moving us in the right direction with less testing and an attempt to make teaching and learning fun again.

Fun again! That’s when education is most effective—when it’s fun. Let us all keep hope.

I agree with what you’re saying Jim, and I realize that returning the testing to the local districts will end up with varying results. The inequities in school funding even within our own state, let alone across the country, result in both high class education and mediocrity, depending on where you live. I just hope that taking more of the federal government out of the decision-making process will help. God only knows schools have so many problems that won’t even be touched by this legislation, but at least it’s a start.