Last week I had a conversation with a local farmer who had dug a well that had a depth of four hundred feet. My mystery-writer brain immediately thought, “Ah, a great place to hide a body.” I was just joking. Well, kind of.

Writers pick up ideas from conversations or news stories, but most often ideas come from quiet reflection. When people ask me where I find my book ideas, I explain that they all begin with thinking. My friend, Kristyne Gilbert, Executive Director of Buchanan Center for the Arts, would say reflection is an essential step in creating.

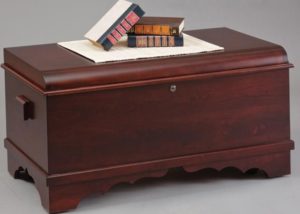

In my current mystery-in-progress, a hope chest is a pivotal object in the plot. My decision to use this object came from a non-linear, twisty, curvy thought process. Bear with me.

My parents during WWII

My granddaughter asked me to look up information for her school history project about World War II. Since my father was in WWII in Germany and France, I pulled several boxes from the bottom of a precariously-packed closet and began going through them. I have my father’s love letters to my mother during WWII, so, of course, I had to re-read those first.

I reluctantly set them aside and came upon photographs of my parents from that time. With those photographs was the attendance book from my mother’s funeral in 1972. So, I opened it and examined the names of hundreds of people who had paid their respects and signed her book. She had died young, so attendance was large and each name brought back memories. Wow! There was a name I had forgotten from my younger days. I’ll just call her Mrs. H.

My brother and me

My mind shifted back to memories of growing up on Kellogg Street in Galesburg across from Cottage Hospital. Next door was a lady whose peony buds were heisted by my older brother to use in his slingshot—one of the few times he ever got in trouble with our parents. That must be why I remember it so vividly—you know, that sibling thing that goes on and on and on? See this wandering mind? Yes, I am getting back to Mrs. H, and then down that curvy road to the hope chest.

Living on the other side of our house was our neighbor, Mrs. H. I don’t know if she was widowed or a “spinster,” but she lived alone, and when I was five or six I thought she must be at least a hundred years old. The neighborhood kids often came to our yard to play ball. I was horribly scared of Mrs. H because whenever our ball went into her yard, she yelled at us.

Later, she had a wire fence built around her yard to keep us out. I was just a kid, and I figured she simply hated us and was always crabby. After the fence divided our yards like sovereign nations, I found an opening where I could go around the fence, stay low, grab the ball, and run home. I’m sure she complained to our parents. Scary, scary, scary.

Then something strange occurred. One day, when I was ten or eleven, my mother said Mrs. H wanted to talk with me at her house. Seriously? Go to her house alone and knock on the door and maybe never come out alive? I didn’t want to go, but my mom made me. Mrs. H asked me into her living room, and she solemnly handed me a package. It was filled with handkerchiefs and dish towels she had embroidered for my “hope chest.” I looked at the meticulous work and couldn’t imagine how many hours she had spent embroidering those linens. Maybe I had misjudged her.

Then something strange occurred. One day, when I was ten or eleven, my mother said Mrs. H wanted to talk with me at her house. Seriously? Go to her house alone and knock on the door and maybe never come out alive? I didn’t want to go, but my mom made me. Mrs. H asked me into her living room, and she solemnly handed me a package. It was filled with handkerchiefs and dish towels she had embroidered for my “hope chest.” I looked at the meticulous work and couldn’t imagine how many hours she had spent embroidering those linens. Maybe I had misjudged her.

I had no clue what a hope chest was, so she explained. This was in the mid-1950s, and the rest of the conversation centered around the cultural values of that time. I’ve never forgotten that day or her conversation about why these items were important to put away in anticipation of my highest female calling in the 1950s: marriage.

For those of you too young to remember, a hope chest (or dowry chest or trousseau chest) was a cedar chest with bed linens, dish towels, handkerchiefs, and other items for unmarried women in anticipation of their future married lives. Strangely enough, these chests were produced, before their last cultural gasp, by a company in Altavista, Virginia, called the Lane Company. I say “strangely enough” because the Lane Company shifted from producing World War I ammunition boxes on their production line to making hope chests after the war. Today, some Amish companies still make these chests. Occasionally, the chests can be found on eBay.

Finally, we reach the end of the thought path. Did I not begin by saying that creativity is a roundabout road?

My new mystery series has a subplot that takes place in the 1960s. A major symbol in this murder mystery will be a hope chest. Its intricate carving will hold a clue, and its contents will reveal aspects of a character who didn’t have a long life.

I would never have thought of this idea if my granddaughter hadn’t asked about my parents and World War II, which led to my father’s love letters, which led to my mother’s funeral book, which led to my brother getting in trouble for the missing peony buds [ha ha], which led to Mrs. H, which led to her kindness and the linens she made for my hope chest. A hope chest—what a great idea to fill a plot hole in my new mystery and serve several other literary uses.

I would never have thought of this idea if my granddaughter hadn’t asked about my parents and World War II, which led to my father’s love letters, which led to my mother’s funeral book, which led to my brother getting in trouble for the missing peony buds [ha ha], which led to Mrs. H, which led to her kindness and the linens she made for my hope chest. A hope chest—what a great idea to fill a plot hole in my new mystery and serve several other literary uses.

There you have it—the extremely meandering pathway from thoughts to words on the page. Kristyne Gilbert would describe this as “the messiness of creativity.” And she would be so right.

Printed with permission of the Monmouth Review Atlas

Great post, Susan. I loved following your meandering mind. My does that, and sometimes I stop and think, “How did I get here?” Then I have to retrace, as you have done, what led to what. Haven’t thought about hope chests in a long time.

Thanks, Judy. I find it really weird the way things just kind of pop in our heads. One thought leads to another, and we wind up in a place we’d never envisioned.

What a wonderful post, Susan. You painted such a beautiful picture of your childhood. Can’t wait to read the book.

Thanks so much, Ellen. The hope chest is in the new series, first book. Working on it! Susan

I love chains of ideas like that, Susan.

My mom’s cedar chest wasn’t her hope chest, but it seems lots of women got them when they married in the 1940s. Hers was in the house all my life, filled with old linens and things. Including the unfinished quilt top made for her as a child by her grandmother. (I stole it from the chest and completed it for her 80th birthday.)

Right now, the chest is in her room at the retirement home, where she just turned 95. It occurs to me I have no idea what’s in it now, if anything. It certainly hasn’t been opened since she moved there 7 years ago. Hmm, chains of thought….

Looking forward to hearing more about your cedar chest plot.

What an interesting story. I think you’d better check out your mom’s cedar chest. This way you can talk with her about the contents. What a wonderful present you gave her for her 80th. I have relatives who quilt, and I sew, but I’ve never been tempted to take up quilting. How fortunate you are to have that gift. The cedar chest plot is currently in the writing stage. I’m hoping to have the book done by late summer. I am sure I’ll be posting things occasionally about its progress. No title yet. Thinking about Chantilly perfume in the title. Or not.