Of Plimoth Plantation, by William Bradford, has an intriguing history. Although it was written from 1630 to 1646, it was never published in its entirety in this country until 1856 as History of Plymouth Plantation. The long pause between writing and publication follows a winding path of theft, political intrigue, and international wrangling. After Bradford’s death in 1657, the manuscript remained with his family for one hundred years. Then it was loaned to Rev. Thomas Prince who used it to write his history. When Prince died, a number of his books and manuscripts were housed in the tower of the Old South Church in Boston. Unfortunately, the British captured Boston and used the church as a riding academy, tearing out the pews and quartering horses in it. When the revolution ended, many of the books that had been kept in the church had disappeared, and one theory is that a British soldier stole the Bradford manuscript.

Of Plimoth Plantation, by William Bradford, has an intriguing history. Although it was written from 1630 to 1646, it was never published in its entirety in this country until 1856 as History of Plymouth Plantation. The long pause between writing and publication follows a winding path of theft, political intrigue, and international wrangling. After Bradford’s death in 1657, the manuscript remained with his family for one hundred years. Then it was loaned to Rev. Thomas Prince who used it to write his history. When Prince died, a number of his books and manuscripts were housed in the tower of the Old South Church in Boston. Unfortunately, the British captured Boston and used the church as a riding academy, tearing out the pews and quartering horses in it. When the revolution ended, many of the books that had been kept in the church had disappeared, and one theory is that a British soldier stole the Bradford manuscript.

Somehow Bradford’s writing ended up in London. [At one time I read that a number of pages had been used to wrap groceries, but I can’t confirm that from a reputable source.] Years after the revolution, it was found in the library of the bishop of London in 1855. It resided in Fulham Palace for many years and was referenced several times in historical writings. Two Boston citizens began a quest for the manuscript after reading the historical references. This began some forty years of legal wrangling because once it was confirmed as Bradford’s work, the bishop of London did not want to give it up. He did allow the Massachusetts Historical Society to publish the words, and 1856 marked the publication of the first complete copy. The bishop stated that only an act of Parliament would force him to give up Bradford’s original manuscript.

In 1867, another request was made to London, and the answer was still no. By 1896, a new bishop of London changed course and allowed the manuscript to be returned to the United States. (Possibly the bad feelings about losing our colonies had subsided by then.) It was placed in the State Library in the archives of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts in Boston. The Boston Historical Society published a complete, authoritative version in 1912, two hundred and eighty-two years after William Bradford sat down to write the history of his beloved colony. It now rests (in surprisingly good condition), in a specially constructed bronze and glass case in the State House in Boston.

In 1867, another request was made to London, and the answer was still no. By 1896, a new bishop of London changed course and allowed the manuscript to be returned to the United States. (Possibly the bad feelings about losing our colonies had subsided by then.) It was placed in the State Library in the archives of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts in Boston. The Boston Historical Society published a complete, authoritative version in 1912, two hundred and eighty-two years after William Bradford sat down to write the history of his beloved colony. It now rests (in surprisingly good condition), in a specially constructed bronze and glass case in the State House in Boston.

The content of Bradford’s book is influenced throughout by the idea that this new land was sustained by God. Bradford describes the desperate trip to Holland to escape the persecution of King James I, and the fears of the Pilgrims when they begin to realize their children are becoming “Dutch” in their thinking and ways. The perilous journey across the ocean is one of his stories, and only God’s help saved them, to land on a hostile and inhospitable shore. In ascribing their safety to God, Bradford tells the story of John Howland who fell overboard, but God caused him to grab hold of a rope, saving his life. As a result, he became a “profitable member of the church and the commonwealth” to the end of his days. One of the most difficult parts to read in Bradford’s history is the story of their first winter when half of the Pilgrims died.

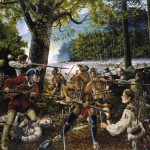

Bradford also described the Indians in many places, and Samoset and Squanto were the natives who saved them the first year and taught them about the geography of their new home. To the Pilgrim’s amazement, they spoke in English, having learned the language from sailors who had visited their shores. Obviously, these positive relationships with the Indians were not to last. Equally sad, he goes on to describe the bloody Pequot War and the slaughter of six hundred Indian men, women and children who died in the fires of their burning village.

Bradford also described the Indians in many places, and Samoset and Squanto were the natives who saved them the first year and taught them about the geography of their new home. To the Pilgrim’s amazement, they spoke in English, having learned the language from sailors who had visited their shores. Obviously, these positive relationships with the Indians were not to last. Equally sad, he goes on to describe the bloody Pequot War and the slaughter of six hundred Indian men, women and children who died in the fires of their burning village.

The last pages of the history are tragic because Bradford’s hopes for a home predicated on God’s words and teachings are dashed when the new arrivals commit crimes and begin to move away from the colony and its religious tenets. English profiteers take advantage of the settlers and the sense of community with which the colony began is sadly dissolving. Bradford ends his narrative with his disappointment that a nation begun with such religious fervor has now moved away from those moral values upon which it was founded.

Bradford’s history was written in what was known then as the Plain Style. This means he used simple words in a clear,  understandable order. The sentence patterns were styled after the Geneva version of the Bible. The Pilgrims preferred that simple style to the more ornate wording of the King James version. Bradford felt the settlers had to concentrate on the essentials, clearly solving problems to enable their survival. The Plain Style seemed appropriate for such a new land.For that reason, he wrote so they could read and understand his words, no matter what their level of education. Eventually, this style would be replaced by such huge figures as Cotton Mather with what became known as the Ornate Style. That style was much more complicated with long, involved sentences. Those sentences included learned references, convoluted phrasing, and parallel sentence structure. It made Bradford’s style read like an elementary school reader.

understandable order. The sentence patterns were styled after the Geneva version of the Bible. The Pilgrims preferred that simple style to the more ornate wording of the King James version. Bradford felt the settlers had to concentrate on the essentials, clearly solving problems to enable their survival. The Plain Style seemed appropriate for such a new land.For that reason, he wrote so they could read and understand his words, no matter what their level of education. Eventually, this style would be replaced by such huge figures as Cotton Mather with what became known as the Ornate Style. That style was much more complicated with long, involved sentences. Those sentences included learned references, convoluted phrasing, and parallel sentence structure. It made Bradford’s style read like an elementary school reader.

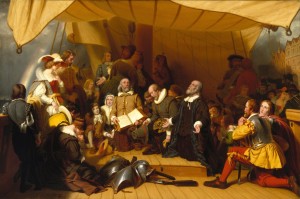

Finally, reading the story of the pilgrims in Bradford’s words is thrilling even today. One of the most famous passages, inspiring the painting, Embarkation of the Pilgrims by Robert Walter Weir, still raises goose bumps when we consider the beginning of this perilous adventure described by the future governor of the colony:

“Being thus arrived in a good harbor, and brought safe to land, they fell upon their knees and blessed the God of Heaven who had brought them over the vast and furious ocean, and delivered them from all the perils and miseries thereof, again to set their feet on the firm and stable earth, their proper element.”

“Being thus arrived in a good harbor, and brought safe to land, they fell upon their knees and blessed the God of Heaven who had brought them over the vast and furious ocean, and delivered them from all the perils and miseries thereof, again to set their feet on the firm and stable earth, their proper element.”

“What could now sustain them but the Spirit of God and His grace?”

I’ve thoroughly enjoyed reading these two posts about Bradford, Susan. Thank you for extending my knowledge of American history.

Happy to share my love of history. Thanks so much for stopping in and commenting. Happy Thanksgiving.

Interesting history on Bradford, the manuscript, and even Plain Language!

Always good to have some idea of why we’re celebrating.