Although both my parents are gone now, I remember them talking about the nights they danced at the Roof Garden on the Weinberg Arcade. Those were magical years, dancing to the songs of the Big Band Era before my father went off to World War II.

Although both my parents are gone now, I remember them talking about the nights they danced at the Roof Garden on the Weinberg Arcade. Those were magical years, dancing to the songs of the Big Band Era before my father went off to World War II.

The story of how the Weinberg Arcade Roof Garden began and the details of what it was like to patronize this dance venue are interesting topics to research. The novella I’m working on, scheduled to come out in April as an e-book from Amazon, will feature a crime committed during the Big Band Era and it will involve such a venue. So besides interviewing long-time resident, Ruth Pecsi [see blog post prior to this one], I also spent time at the Galesburg Public Library researching with the help of Patty Mosher, archivist. The search brought me a rich load of details about going to the RG, and it also divulged highlights of the history of these kinds of venues. This was a place my parents often attended, and it must have been a wonderful experience during and after the Depression.

The Big Band Era spanned 1935 to 1945 and the Weinberg Arcade Building found itself in the thick of things because of the

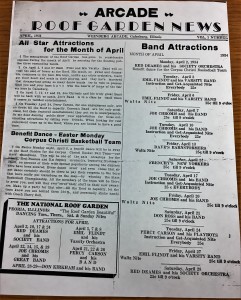

The newsletter of the Roof Garden

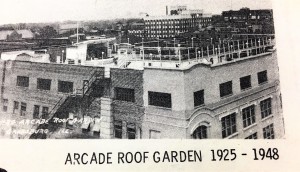

foresight of several early Galesburg, Illinois residents. It was also a perfect example of necessity being the mother of invention. Towns in the area that had roof gardens for dancing included Champaign, Peoria, Sterling, and Macomb. In Galesburg, the Weinberg brothers built the Weinberg Arcade in 1922. It was three stories high with a full basement(although later they added a fourth story.) This building housed many offices and stores, but it also had a silent movie theater, the West Theater. W. R. (Rollo) Allensworth and Harlan Little owned both the movie theater and a ballroom one story above it. When “talkies” came in at the movie theaters, the patrons couldn’t hear the dialogue because of the music from above in the ballroom. So Allensworth convinced his cousins, the Weinbergs, to let them open the roof of the building for dancing.

… And so, the plans for this magical venue began. They tore up the roof, water-proofed it, and laid down a composite, marble-like flooring. For safety, they added a fence around the sides of the roof. The floor was very hot from the sun until after dark. Then, because of wax, it was slick, and dancers needed rubber soles on their shoes. On hot summer nights, a cool breeze blew across the dance floor, and patrons sighed with relief in the years before air-conditioning.

The décor has been described and photographed as has the crowded dance floor. Lights were placed 12 to 15 feet apart and mounted on firewalls. They were red, blue, and green, so when patrons walked off the elevator they saw an amazing, twinkling wonderland. A band shell was set up with chairs for the musicians, a piano, and spotlights, and along the edge of the dance floor were benches and sofas. Dancers could see a panoramic view of the city as they waltzed around the floor. (Good thing they put up fences around the edge.) As many as 1200-1500 people attended costumed Halloween dances, and on Friday or Saturday nights, before the war, often 1,000 people attended. But, if you didn’t have the price of admission, you could dance below under the streetlights to the music filtering down from above.

The décor has been described and photographed as has the crowded dance floor. Lights were placed 12 to 15 feet apart and mounted on firewalls. They were red, blue, and green, so when patrons walked off the elevator they saw an amazing, twinkling wonderland. A band shell was set up with chairs for the musicians, a piano, and spotlights, and along the edge of the dance floor were benches and sofas. Dancers could see a panoramic view of the city as they waltzed around the floor. (Good thing they put up fences around the edge.) As many as 1200-1500 people attended costumed Halloween dances, and on Friday or Saturday nights, before the war, often 1,000 people attended. But, if you didn’t have the price of admission, you could dance below under the streetlights to the music filtering down from above.

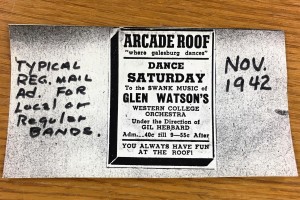

The nights and the cost of dancing varied depending on the year. When it opened, the RG had dances on Tuesday, Friday  and Saturday, and later it opened four nights a week. When the city council would not let them open on Sunday, the owners organized a dance that started one minute after midnight and went until 4:30 a.m. on Monday morning. Couples often wandered over to the Burlington Train Depot for breakfast. (I wonder if they were all falling asleep at their jobs on Monday.) The costs also varied depending on the year. Admission was generally 25 cents to get in and 10 cents a dance. A stamp on your hand said you’d paid admission.

and Saturday, and later it opened four nights a week. When the city council would not let them open on Sunday, the owners organized a dance that started one minute after midnight and went until 4:30 a.m. on Monday morning. Couples often wandered over to the Burlington Train Depot for breakfast. (I wonder if they were all falling asleep at their jobs on Monday.) The costs also varied depending on the year. Admission was generally 25 cents to get in and 10 cents a dance. A stamp on your hand said you’d paid admission.

And what about the music? Long-time residents of Monmouth, Gracie Peterson and her sister, Alice Nevius, (the Gawthrop Sisters), provided music early on, and I found an interview stating they had been the musical entertainment on July 16, 1925. Then the big bands played there, and they included Kay Kyser, Bob Crosby, Count Basie, Tiny Hill, Tommy Dorsey, Paul Whiteman, Bix Beiderbecke, and Frankie Trumbauer. Local bands also played.

Various phone interviews in the archives spoke to the human experience of going to the Roof Garden. During Prohibition, alcohol was prohibited, but often the guys brought flasks or ½- pint bottles in their pockets. Behavior was guided by definite expectations: no fights and no public displays of affection. Clothes ranged from “dressed up” in suits and dresses on  Saturday night, to school clothes for the younger folks. Both local institutions—Knox College and the Mayo Army Hospital—had ROTC cadets and soldier/patients who attended in uniform during the war.

Saturday night, to school clothes for the younger folks. Both local institutions—Knox College and the Mayo Army Hospital—had ROTC cadets and soldier/patients who attended in uniform during the war.

However, the war eventually changed everything. Men left by the troves. Bands went into special service or lost members to the draft, and once the war ended, families began staying home on the weekends to raise children and watch something new called “television.” [Probably the reason for the fall of western civilization as we know it.]

I think, however, if I close my eyes, I can see my parents in their twenties, dancing to the strains of “In the Mood,” “Moonlight Serenade,” and “I’ll Never Smile Again.” They always said this was a magical oasis in the middle of the Depression and the years leading up to the war when my father went into the army. That led, of course, to the best thing that ever happened to them with the birth of the first Boomer kids in 1946.

I think, however, if I close my eyes, I can see my parents in their twenties, dancing to the strains of “In the Mood,” “Moonlight Serenade,” and “I’ll Never Smile Again.” They always said this was a magical oasis in the middle of the Depression and the years leading up to the war when my father went into the army. That led, of course, to the best thing that ever happened to them with the birth of the first Boomer kids in 1946.

I so enjoyed this post and the photos! I remember watching The Glen Miller Story as a kid at our cottage (we only got one channel, and the movies they showed were all from the 1950s). I’ve actually looked for that movie since, but it’s never come back. Love In The Mood and have it on my iPod, right after Maroon Five 🙂

Thanks so much for your comment, Judy. I remember watching that movie with my dad shortly before he passed away. We both knew how it was going to end, so it was a bit like watching the last half of “The Titanic,” but we enjoyed it. What an amazing time that was. I’ve enjoyed researching it.

Thanks for posting this article. I appreciate the glimpse into the past. I imagine the dancers were tired on Monday morning, but when I was in my twenties I could stay up till 3 AM almost every night and then report for work at 8. Enthusiasm can take you a long way.

Good reminder, Sarah. Yes, I can see my parents doing that in their younger days. I’m glad you enjoyed this look back into history. Thanks for your comment.

Susan, I wrote a memoir for the Sandburg Competition several years ago. I wrote it about the 1950’s in Galesburg, which, of course, was our era. In that memoir, I referred to us baby boomers as “products of passions deferred by war.”

Yes, ma’am, the ’40’s was the decade we got our start, and reading about it all seems so romantic now. Naturally, it seem so romantic because i don’t really remember any of it. That’s why I am enjoying your posts so much: a little glimpse of my parents’ era.

But, hey, we must keep in mind that there was a murder–cold case–committed in the era of bobby socks and swing. Where? Right in Endurance!

And, as an upright citizen born in ’46, I want that case solved before I am gazing day and night at Henry Hill Correctional Center after being planted in Brookside Cemetery.

Jim, you are so funny. I promise you the case will be solved in about 100-120 pages. I would not want to think of you lying beneath the daffodils worrying about this. I, too, found it great fun to think of my parents dancing here in the 1930’s and 1940’s, and I love your description of us baby boomers as “products of passions deferred by war.” The great family myth (maybe myth) was that my dad played poker on the ship home to buy my first baby shoes. [I think that was some of his blather.] But it was a nice thing to tell a daughter born right after the war. I’ve had a lot of fun researching this dance venue and it will come in handy in my book.